‘A New Story Told Out of an Old Story’ by Cathy Sweeney

1. The Woodcutter

Once upon a time there lived a man who cut trees for a living. He was a big man, strong as an axe, and everyone called him the woodcutter. On account of his strength no one expected him to be clever, not even himself. But he was clever and before long he was engaged to marry the miller’s daughter. She was a plain girl but a fine catch. There was only one problem. The woodcutter was afraid the miller’s daughter would hear the story told in the village. She had of course heard the story before, a hundred times, but no one ever really hears a story until they need to. The woodcutter worried that the miller’s daughter would break the engagement. His fear kept him up at night. He knew that the only way to sleep soundly was to tell the story to the miller’s daughter himself. And so he did.

2. The Story The Woodcutter Told The Miller’s Daughter

A long time ago there lived a young woman who was happily married and had a child in a cradle. One day she went walking alone in the forest. Darkness fell and the woman realised that she had strayed deep into the forest far from home. A wolf appeared. He attacked the woman, scraping his paw down one side of her face and scarring her forever, but luckily she managed to run away. When she arrived home her husband could not bear to look at her and shortly afterwards he disappeared and was never heard of again. The woman moved into an old run-down cottage on the edge of the village and took in washing to earn enough money to feed herself and her child. At first the villagers were generous towards the woman, bringing her lightly soiled clothes and paying her well, but later, galled by her refusal to engage in self-pity, they turned against her, and brought her their stained underclothes and dirty bedsheets and haggled over payment. The woman’s child, a girl, grew up and married a man who was new to the village, but when he heard the story of the wolf the man disappeared and was never heard of again, leaving his wife with a child in a cradle.

3. The Grandmother

When he reached the end of the story the woodcutter, as you might expect, revealed that the woman walking in the forest was in fact his own grandmother and her child his own mother. The miller’s daughter was delighted. And because she was delighted, the woodcutter too was delighted. However, lying in bed that night, unable to sleep, his thoughts turned to the story he had not told. To free himself of such thoughts he did what most people do. He told himself a much more pleasant story, about a girl who fell in love with a wolf, putting in plenty of red and pink detail, until he attained the relief such storytelling usually brings. And then he fell asleep.

4. The Clever Girl

The woodcutter and the miller’s daughter were married. They were blessed with three boys, strong as axes, and one clever girl. Apart from the nightly tossing and turning in bed, the woodcutter was content, and in the evenings he enjoyed telling stories by the fire. The clever girl preferred stories about real people and real life but her father preferred the once upon a time kind, favouring variations on a theme involving a hero who escaped a lowly past to live a life of fortune. Years went by. The strong boys grew up to cut wood for a living while the clever girl walked in the forest, the only thing her father had forbidden her to do. They very nearly lived happily ever after. Except that one day the clever girl disappeared and was never heard of again. The story in the village was that she had run away with a wolf.

5. The Story

When it is too late we all want to tell the whole story. And so it was with the woodcutter. Broken hearted, he went to see the priest with the intention of pouring it all out, every last drop of the story, so that at last he would be would be able to sleep at night. And so he did.

6. The Story The Woodcutter Told The Priest

My grandmother was a black-eyed woman. I grew up not far from her cottage on the edge of the village but I hardly knew her. She kept to herself. From time to time my mother sent me to her cottage on errands and each time my grandmother would invite me in, sit me at the table, serve me stale bread and a glass of sour milk, and then tell me to go. There was never any fire in my grandmother’s cottage. Just a grate with smoke in it. On the dresser, a few assorted cups and plates. A withered piece of fruit in a bowl. An ancient metal tea caddy with a small wooden spoon attached to it by a string. Rolled-up newspaper plugged gaps in the floor. A kerosene lamp flickered in the corner. There were no pictures. The story in the village was that my grandmother had once been attacked by a wolf and had scars all over her body. My mother would never tell me if the story was true or not but everywhere I went as a child I heard wolf whistles.

7. The Priest

The priest listened quietly. He said nothing. When the man left he opened a drawer in his desk and took out a folded yellow paper. Years before when he was a young curate and easily shocked, he had visited the woodcutter’s grandmother on her deathbed. When he arrived she was very weak and her mind was running like an old clock, too fast and too slow, but he swore to her that he would write down what she said, word for word, as best as he could. And he did.

8. The Story The Grandmother Told The Priest

Night falls differently in forests. Darkness pauses at the tops of trees, and then drops thick and heavy, like a guillotine. It was in that time, when charcoal smudges the last light, that I first saw the wolf. He smelled like a butcher’s shop. Sharp. Old blood soaked in sawdust. The more you inhale the less you smell, but when you relax your nostrils they are flooded with it. When I saw the wolf I closed my eyes and circled my hands around the trunk of a tree, strong and rough against the smoothness of my skin. I hated my husband. Putty fingers. Shallow eyes. Mouth made for eating dead things. I wanted the wolf. Each day I went further into the forest. Sometimes I saw him. Shadow in trees. Black eyes staring at blackness. A creature of habit. It could have gone on forever. Always longing. Never reaching. But one evening, just before night fell, I heard the cry. There was a strange swelling in the trees, dark and malevolent. Above my head branches bent and groaned. Faster and faster I ran. My breath in and out like frozen waves. When I found the wolf I forced the metal from his flesh and carried him back to the den. I nursed him. Sad eyes and a smell like old rain. Then I seduced him. Slow strokes of bristled fur, my lips on the inside velvet of his ear. Days of hunting, killing, eating. Reading newspapers. Winding clocks. Lighting lamps. Smoking by the fire. The way we curled together to sleep. When the men came I said nothing. I watched the wolf close his mind. I think he drooled. I said nothing when the men looked at me in my petticoat. They killed the wolf. Spots of blood on my petticoat. His tail hacked off to be nailed to the wall in the jailhouse. My husband couldn’t look at me but wanted me harder than before. Later I stole the wolf’s tail from the jailhouse and sewed it to my skin under my breasts where no one could see it. One stitch every day, each one weeping and bleeding, scabbing and healing, until the tail and my flesh became one and my husband disappeared.

9. The End

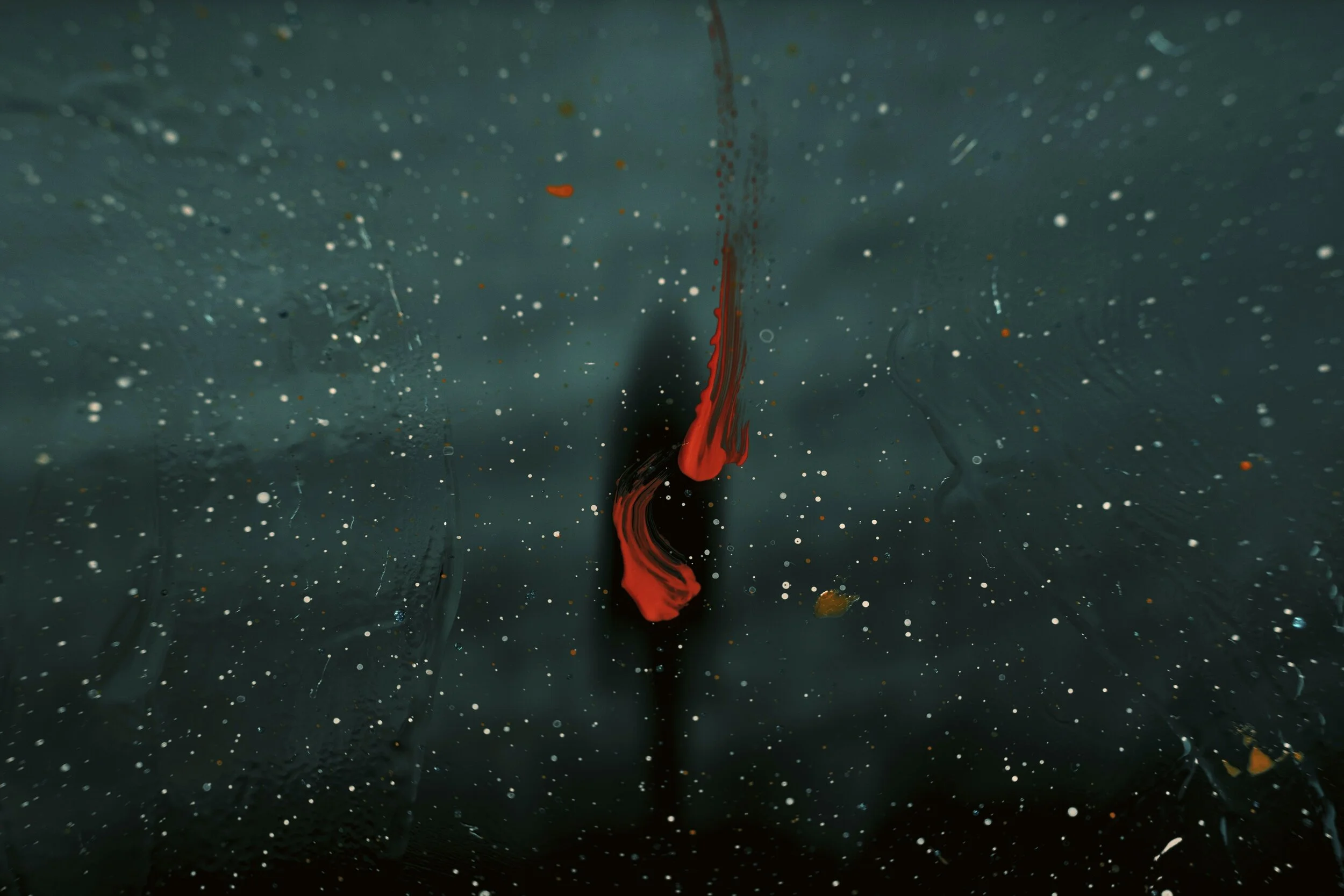

The priest folded up the yellow pages and threw them in the fire. Although it was late he put on his coat and hat and walked out, past grocery stores, empty bars, villagers with shallow eyes. Mud. The earth hardened and raw. Cattle moaning low in far fields. The savagery of nature. Splashes of colour like wounds. He walked through dry leaves, over branches ragged in moonlight, through visions of doomsday, passed hunger and thirst and desire. The clack-clack of work. A dog barking. Wind rattling the houses of the poor. Through the fumes of memory and out the other side of dream. On and on beyond the black trees until the sky was as white as a page.

From issue #5: autumn/winter 2017

About the Author

Cathy Sweeney is a writer living in Dublin. Her short fiction has been published in The Stinging Fly, The Dublin Review, Egress, Winter Papers, The Tangerine and has been broadcast on BBC Radio 4. Her debut short story collection Modern Times is published by the Stinging Fly Press and Weidenfeld & Nicolson. She is at work on a novel.