‘Better, Sweeter’ by Jayne A. Quan

My partner and I haven’t been together for very long, despite the fact that we’ve known each other since 2011. We only really started becoming a thing six days before I was scheduled to have my bilateral double mastectomy. With all the love and care I thought only existed between two people who had been together for a long while, she made me a number of portioned, low sodium meals to eat after my surgery. She gave them to me sheepishly.

‘I’m not sure how good they’ll taste,’ she said. ‘They’re a little bland without salt.’

At the time, I lived with my parents and one might ask why my parents didn’t make me portioned, low sodium meals to eat after my surgery. I’m not sure that it’s a valid question. Sometimes, people don’t need excuses for not thinking in advance to do something. I don’t really blame them either. I can’t, in fact. It would seem unfair of me to do so.

*

My brother, only ten years old, died in November 2017. That was eight months before my surgery. Our family seemed to implode with such force that it exploded too – the big bang. The death of my brother was the birth of an alternate universe for us: one in which he did not exist. We lived in parallel realities from our timeline when he was with us to the timeline we have now found ourselves in.

Sometimes, I think that I was the only person who knew he was going to die.

He’d been sick since he was born, an extremely premature birth at twenty- two weeks and five days gestation. At ten years old, he needed a lung transplant to keep going. Half of all patients who receive a lung transplant don’t make it a full year. He had only one working lung when he was placed on the list. Everything seemed against him. But what kind of people would my family be if they did not possess optimism despite these odds?

At times, I saw myself as a monster for thinking that he was not going to make it. That he would not get the transplant, or worse, that he would, and he would simply die on the table. I stopped myself short of thinking of that borrowed time that we could manage to get out of someone else’s lung. My brother, who I love so dearly, so ardently, was never old in my imaginations of him. I had never allowed myself to see him as an adult, as a teenager graduating from high school, as anything but that ten-year-old boy with the crooked teeth.

I loved him – still do – and I never let myself think of what he would look like if he had gone through puberty.

*

Taking testosterone made me ravenous.

I ate everything I could. Every free dessert, snack, or meal offered by my place of work seemed to find its way into my hands, into my mouth. I had the appetite of a teenage boy but without the metabolism of one.

I never knew what contributed most to my weight gain: the testosterone or my depression. I was set to leave New York, to move back home to California to help my family while my brother relocated to Texas to wait for his lung transplant. I think I knew even then. I think I halted my thoughts, even then, as I packed up and readied to move out and return to the west coast.

My body changed, grew, rounded as I packed up my things, figured out the logistics of my going. My shirts became too tight and my feet grew a whole size. I felt as though even the ring I always wore became too tight on me.

Many of the changes in my physical composition were expected changes, mildly anticipated ‘side effects’ of taking testosterone. There were emotional alterations, too, though I can’t say for certain what was the deciding factor in my mood swings and brain chemistry altering just ever so slightly – the testosterone or my move? What led me down, dragged me quietly and eerily into the place that I felt my real self slept in?

I found it increasingly difficult to express joy. The words that came out of my mouth had thoughts that I knew were sincere but something about my delivery seemed flat, deadened. I told people I would miss them but it felt like I was dying instead of going away. And then, suddenly, white hot flashes of anger about my situation, about my brother’s life, about the unfairness of health. Just as suddenly it would all flatline again.

I’ve never told anybody this, but I’ve always had the feeling that because of that move, I would never come back to live in New York.

*

My brother was a normal boy except for the fact that he had a nasal cannula and a tank of oxygen with him at all times. When he was younger, he had a few fine motor skill problems, but as he got older those things went away. He played piano and ukulele, though he fought you when you told him it was time to practice. He would have much rather been playing on a screen. A normal boy.

He had a food therapist come in to work with him all the time. One of the things that was not normal for a normal boy, I guess. It was normal for us – this man coming to teach my brother to eat and swallow; he showed up and chatted, became friends with our family. The night before we flew out to Texas, he came to pick up and care for our dog while we had to be away.

My brother had chewing exercises. He had the tendency to keep things in his mouth and not swallow them. We thought it was partly psychological. He was, after all, adept at eating things like ice cream and candy without being reminded of having to swallow or chew properly or eat a certain amount. He liked sweets and that was about it. The pickiest eater in our whole family.

When it got really bad, when he needed calories but wasn’t so great at eating, we would pump caloric-heavy formula into his gastronomy tube. When he got older, we would try to get him to drink it, but he hated the way it tasted. I couldn’t blame him – to be fair, I tried it once. It didn’t taste great. Sometimes we would have to give him some of his formula while he was asleep, through the g-tube. He would never wake up during this process and I still have an alarm in my phone with its label telling me to feed my brother his formula.

I don’t know what his last meal was. I’m not sure any of us do. I don’t think it was one of those things we thought of and I feel like it would be weird and disrespectful if I asked about it now. But I wonder about it, sometimes, if it was the formula he hated so much, or something better – something sweeter.

When we arrived at Texas Children’s Hospital, he was intubated. I believe the last words I said to my brother were on a FaceTime while he was still conscious.

‘I love you! I miss you!’

And then the infection got worse and off we went, the rest of our family, to Houston to watch my brother cleave our universe into a timeline where he could no longer stay.

The last words I said to my brother, while he was unconscious, when they removed his breathing tube ... I don’t remember. It might have been the same; it must have been the same. But I wish it had been something better, something sweeter.

*

When I woke up from my surgery, the nurse handed me a popsicle. It turned my tongue bright red. I had a tube down my throat for four hours, maybe more. They said it took me a while to wake up after the anaesthesia wore off.

She told me as soon as I was done with one popsicle, she could get me another. I ate four by the time I was able to dress myself in the bathroom and they helped me to the front of the hospital in a wheelchair. My friend who drove me to the hospital then drove me back to my parents’ house. I fell asleep halfway through, sated by painkillers.

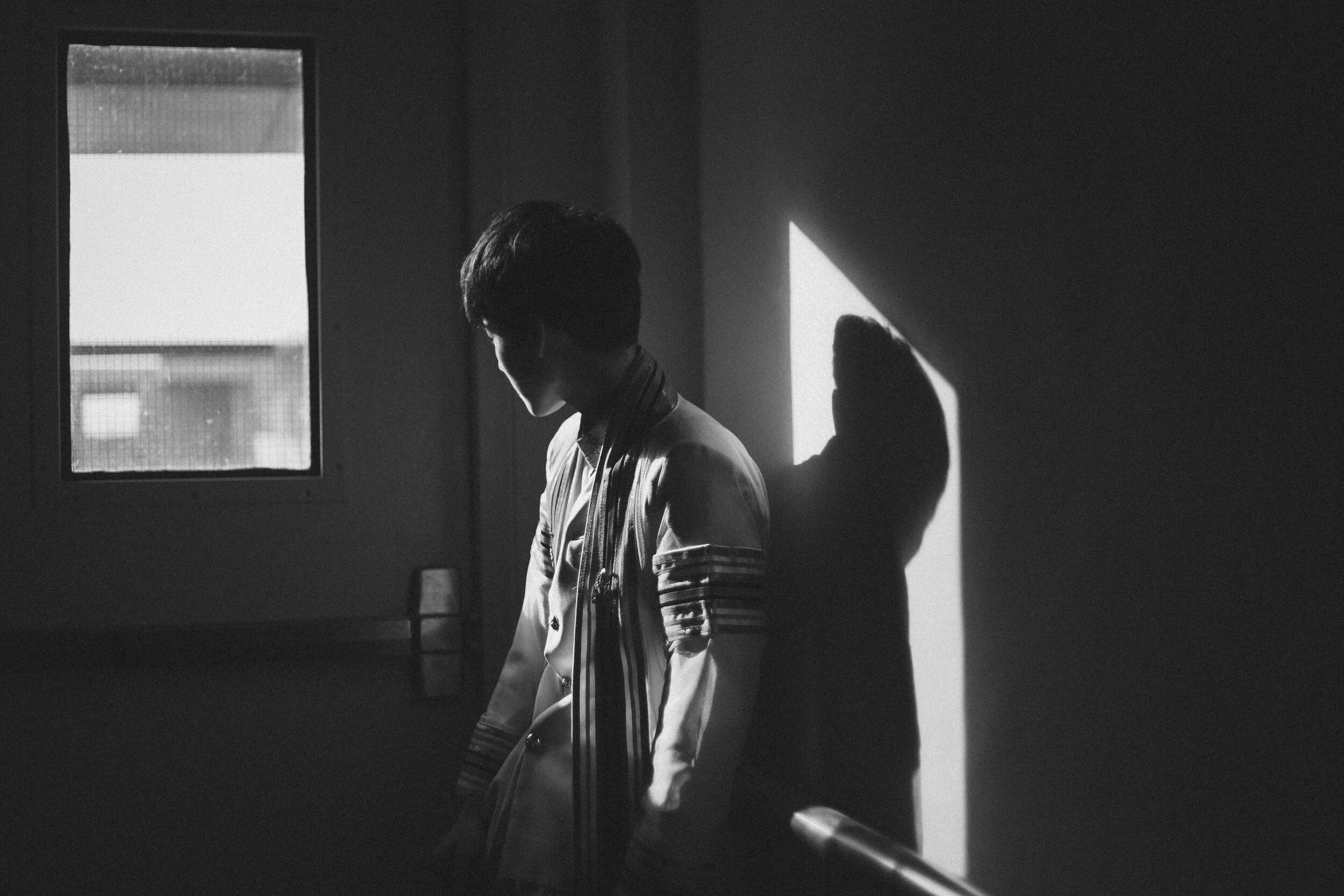

My partner says she’s mad she wasn’t there for me when I got my surgery. She planned a family trip to the east coast before we were a thing. I think, even though we weren’t a thing long before my surgery, she loved me then, mostly because I loved her then, too. It’s difficult for us to explain how we got from Point A to Point B, how to explain to our friends how we happened. Even after such a short amount of time we both feel like our story is longer and richer than what it really is.

What brought us so close together?

After my brother died, it was difficult to find joy and meaning in anything in my life. I went to therapy every other week to try and make sense of living. I had problems at home, things I find difficult to put into words, not because the wound is fresh, but because I feel as though I cannot blame my family for the ways that we treated each other. It was worse than being feral, than lashing out at one another. We were like black holes, each one of us, sucking the light out of everything, growing dense with sorrow.

The lowest I had ever thought to be – that’s when my partner let me in.

I wasn’t really allowed to have sex so close to having had a major surgery. I ate the low-sodium meals my partner prepared to keep the swelling down and texted her every morning, giving her updates on my aches and pains, showing her pictures of my bruising. She came back from the east coast a week into my recovery, thirteen days after we first started to become a thing.

Beautiful and shy, she laid next to me, careful of my post-surgery drains and still-sore torso. Did I think about how I could finally lay next to her in a body that more closely resembled how I felt? I don’t know. All I know is that she laid next to me and then we gave ourselves to each other, possibly against doctor’s orders. I want to say something stupid, something like: it felt like having sex for the very first time. But it was not that. It just felt right. Right in a way that I don’t have words for. That I don’t think many people have words for, when they experience a life affirming surgery and then lay next to someone they think they might be falling in love with.

I missed her, even though it was such a short amount of time, I missed her. I needed her, in a way. It wasn’t dependency, except that maybe it was. Maybe I did depend on that feeling that she gave me, the feeling that life really was going to keep moving on. She did not save my life the way people might want to romanticize it. What she gave me was something as close to living as I had felt since my brother had died. Something more than just surviving.

Something better.

Something sweeter.

*

My partner and my brother had never met.

They will never meet.

They are two tines in the split fork of my life, running parallel to each other. I imagine them as physical embodiments of the alternate universe I felt crack and splinter off when my brother died. One is where he was, the other is where she will be.

It’s difficult to think that two people who mean so much to you can never look one another in the eye. I have to tell her what he was like, recounting stories of him through the laughter of reminiscing. But I can’t tell him about her. I can tell her about the funny things he said or did, but I can’t tell him about how I think she’s the smartest woman I’ve had a conversation with. That I find it endearing when she admits she doesn’t understand a pop culture reference. That I love her even though she leaves the refrigerator open while she rummages about in the kitchen.

I don’t think my partner and my brother were ever supposed to meet.

At least, I convince myself of thinking that way because it seems easier than the alternative, as if an alternative was ever within our grasp. It’s easier to think that this is how it’s supposed to be, than to give myself permission to imagine an alternate timeline where they are in the same room, laughing. Even if I did give myself permission to imagine it, it’s hard to know where to begin. I feel that, even though I was so sad, even though I felt so despondent to living, I can’t imagine how my partner and I would have happened had it not been for those unfortunate circumstances.

How did we get from the Point A of our friendship to the Point B of our relationship?

How did time move on after my brother died?

I was able to receive top surgery because I came to California to help my family as my full-time job. Without that, I would not have been able to get onto Medi-Cal, the medical insurance that covered the cost of my double mastectomy – something that I was nowhere near able to afford prior to that coverage. Had my brother not died, I wouldn’t have found a therapist who was able to connect me within my network to my surgeon, on top of working with me on my mental health. Had I not had my surgery and that access to therapy, would I have truly known the tender beginnings of a blossoming love between myself and my partner?

It’s hard to say.

Karen Blixen once wrote: ‘I know the cure for everything: salt water – sweat, tears, or the salt sea.’ I think about all the salt in my life. The tears and the sweat, the Pacific Ocean which I grew up so close to and the Atlantic which I tried to make work from both ends. I think about all the times I could not cry when I first started testosterone, an effect they’d warned me about. I think about all the tears after my sweet brother passed on. I think about the sweat I poured trying to tune my body toward something I could claim as true to my sense of self as I could get. I think of the fact that my brother and my partner have never met, can never meet. What could cure that? What could possibly cure that hurt?

And then I think of my partner, who handed me a bunch of meals and said, ‘They’re a little bland without salt’. I think of the way she asks me to tell her something else about my brother. I think of the way her eyes well up with tears when she listens or the way she laughs with me as I talk. I think of the way she asks about the scene, like she’s truly recreating it in her mind.

I think, is the cure to everything truly salt water?

Or is it something better, something sweeter?

From issue #10: autumn/winter 2020

About the Author

Jayne A. Quan (they/them) writes non-fiction and poetry. They’ve recently completed an MA in Creative Writing at University College Dublin. They are (in no particular order) transmasculine, non-binary, queer, and Asian American. Most controversially, they claim to love cats and dogs equally.